-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage

La lecture à portée de main

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisDécouvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisEn savoir plus

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

En savoir plus

Description

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Part I: Dakota Boarding-School Autobiographies

1. Charles Eastman's From the Deep Woods to Civilization

2. Luther Standing Bear's My People, the Sioux

3. Zitkala-Sa's "Impressions of an Indian Childhood," "The School Days of an Indian Girl," and "An Indian Teacher among Indians"

4. Walter Littlemoon's They Called Me Uncivilized, Tim Giago's The Children Left Behind, Lydia Whirlwind Soldier's "Memories," and Mary Crow Dog's Lakota Woman

Part II: Ojibwe Boarding-School Autobiographies

5. John Rogers's Red World and White

6. George Morrison's Turning the Feather Around

7. Peter Razor's While the Locust Slept

8. Adam Fortunate Eagle's Pipestone: My Life in an Indian Boarding School, Dennis Banks's "Yellow Bus," and Jim Northrup's "FAMILIES—Nindanawemaaganag"

9. Edna Manitowabi's "An Ojibwa Girl in the City"

Part III: A Range of Boarding-School Autobiographies

10. Thomas Wildcat Alford's Civilization

11. Joe Blackbear's Jim Whitewolf: The Life of a Kiowa Apache Indian, and Carl Sweezy's The Arapaho Way: Memoir of an Indian Boyhood

12. Ah-nen-la-de-ni's "An Indian Boy's Story"

13. Esther Burnett Horne's Essie's Story

14. Viola Martinez, California Paiute: Living in Two Worlds

15. Reuben Snake's Your Humble Serpent

Appendix A: A Letter from Thomas Wildcat Alford, a Returned Student Formerly at Hampton Institute

Appendix B: Indian Boarding-School Students Mentioned in This Study, Vols. 1 and 2

Notes

Works Cited

Index

Sujets

Informations

| Publié par | State University of New York Press |

| Date de parution | 01 septembre 2020 |

| Nombre de lectures | 2 |

| EAN13 | 9781438480084 |

| Langue | English |

| Poids de l'ouvrage | 1 Mo |

Informations légales : prix de location à la page 0,1748€. Cette information est donnée uniquement à titre indicatif conformément à la législation en vigueur.

Extrait

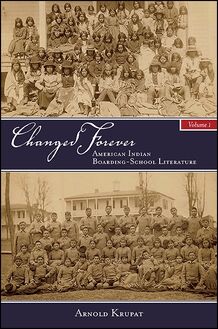

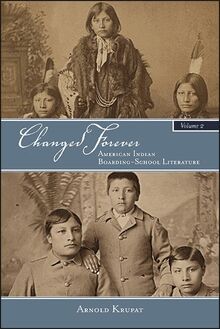

C HANGED F OREVER Volume II

SUNY series, Native Traces

Jace Weaver and Scott Richard Lyons, editors

Changed Forever

Volume II

A MERICAN I NDIAN B OARDING -S CHOOL L ITERATURE

Arnold Krupat

On the cover: Chauncey Yellow Robe (Timber), Henry Standing Bear, and Richard Yellow Robe (Wounded) at the time they entered Carlisle Indian School in 1883 and three years later, in 1886, both photographs taken by John N. Choate. Courtesy of Dickinson College Carlisle Indian School Project.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

© 2020 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Krupat, Arnold, author.

Title: Changed forever: American Indian boarding-school literature. Volume II / Arnold Krupat. Other titles: American Indian boarding school literature

Description: Albany, NY : State University of New York Press, [2020] | Series: SUNY series, Native traces | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017022009 (print) | LCCN 2018005523 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438480084 (e-book) | ISBN 9781438480077 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Off-reservation boarding schools—United States—Biography. | Boarding school students—United States—Biography. | Indian students—United States—Biography. | Hopi Indians—Biography. | Navajo Indians—Biography. | Apache Indians—Biography. | Autobiographies—Indian authors.

Classification: LCC E97.5 (ebook) | LCC E97.5.K78 2018 (print) | DDC 371.829/97—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017022009

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Gerald Vizenor

What has become of the thousands of Indian voices who spoke the breath of boarding-school life?

—K. Tsianina Lomawaima

We still know relatively little about how Indian school children themselves saw things.

—Michael Coleman

Boarding-school narratives have a significant place in the American Indian literary tradition.

—Amelia Katanski

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Introduction

P ART I D AKOTA B OARDING -S CHOOL A UTOBIOGRAPHIES

1 Charles Eastman’s From the Deep Woods to Civilization

2 Luther Standing Bear’s My People, the Sioux

3 Zitkala-Sa’s “Impressions of an Indian Childhood,” “The School Days of an Indian Girl,” and “An Indian Teacher among Indians”

4 Walter Littlemoon’s They Called Me Uncivilized , Tim Giago’s The Children Left Behind , Lydia Whirlwind Soldier’s “Memories,” and Mary Crow Dog’s Lakota Woman

P ART II O JIBWE B OARDING -S CHOOL A UTOBIOGRAPHIES

5 John Rogers’s Red World and White

6 George Morrison’s Turning the Feather Around

7 Peter Razor’s While the Locust Slept

8 Adam Fortunate Eagle’s Pipestone: My Life in an Indian Boarding School , Dennis Banks’s “Yellow Bus,” and Jim Northrup’s “ FAMILIES — Nindanawemaaganag ”

9 Edna Manitowabi’s “An Ojibwa Girl in the City”

P ART III. A R ANGE OF B OARDING -S CHOOL A UTOBIOGRAPHIES

10 Thomas Wildcat Alford’s Civilization

11 Joe Blackbear’s Jim Whitewolf: The Life of a Kiowa Apache Indian , and Carl Sweezy’s The Arapaho Way: Memoir of an Indian Boyhood

12 Ah-nen-la-de-ni’s “An Indian Boy’s Story”

13 Esther Burnett Horne’s Essie’s Story

14 Viola Martinez, California Paiute: Living in Two Worlds

15 Reuben Snake’s Your Humble Serpent

Appendix A A Letter from Thomas Wildcat Alford, a Returned Student Formerly at Hampton Institute

Appendix B Indian Boarding-School Students Mentioned in This Study, Vols. 1 and 2

Notes

Works Cited

Index

ILLUSTRATIONS

1 Superintendent Richard Pratt and Carlisle staff

2 Plenty Horses in 1891

3 Charles Alexander Eastman in 1897

4 Charles Alexander Eastman in 1913

5 Frontispiece of Stiya, a Carlisle Indian Girl at Home

6 Luther Standing Bear with his father

7 Spotted Tail’s delegation to Washington in 1880

8 The elder Standing Bear with his children and a friend at Carlisle

9 Dennison Wheelock, cornetist and conductor of the Carlisle Band, 1890

10 Zitkala-Sa in “traditional” dress

11 Zitkala-Sa with her violin

12 An Ojibwe chief outside a Medicine Lodge

13 Peter Razor in 2014

14 The first Indian graduates of the Hampton Institute in 1882

15 Joe Blackbear, Anadarko, Oklahoma, 1948

16 The Reverend H. R. Voth with a group of Arapaho girls

17 Carl Sweezy

18 Esther Burnett, about 1925

19 Reuben Snake, New York City, 1992

INTRODUCTION

FROM THE MOMENT THEY SET FOOT UPON THESE SHORES, THE EUROPEAN invader-settlers of America confronted an “Indian problem.” 1 This consisted of the simple fact that Indians occupied lands the newcomers wanted for themselves. To be sure, this was not the case for the earliest Spanish invaders of the Southeast and Southwest in the mid-sixteenth century, whose intent was to find treasure and to convert and missionize the tribal peoples they encountered. But in the Northeast, the English, from the early seventeenth century, and then the Americans, as they made their way across the continent, came to understand that broadly speaking, America’s Indian problem permitted only two solutions: extermination or education. Extermination was costly and dangerous, and in time it came to be thought wrong.

It then began to appear wiser, as the title of Robert Trennert’s introduction to a study of the Phoenix Indian School put the matter, for policymakers to proceed according to the assumption that “The Sword Will Give Way to the Spelling Book” (1988 3), thus offering—again to cite Trennert—an “alternative to extinction” (1975). Educating Native peoples—teaching them to speak, read, and write English; to convert to one or another version of Christianity; and to accept an individualism destructive of communal tribalism, ethnocide rather than genocide, was a strategy that might more efficiently and with fewer pangs to the national conscience free up Native landholdings and transform the American Indian into an Indian-American, uneasily inhabiting if not quite melted into the broad pot of the American mainstream.

In a fine 1969 study, Brewton Berry remarked that so far as the choice between “coercion” and “persuasion” was concerned (23), “Formal education has been regarded as the most effective means of bringing about assimilation” (22). In these respects, Trennert writes, when the Phoenix Indian School was founded in 1891, it was “for the specific purpose of preparing Native American children for assimilation … to remove Indian youngsters from their traditional environment, obliterate their cultural heritage, and replace that … with the values of white middle-class America.” Complicating the matter, he adds, was the fact that “the definition of assimilation was repeatedly revised between 1890 and 1930” (1988 xi). 2 Further complicating it well in to the 1960s and beyond was the fact that “white middle-class America” was not generally willing to accommodate persons of color regardless of whether they shared its values or not.

In the Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1890, the “Rules for Indian Schools” stated clearly that the government, in “organizing this system of schools,” intended them to “be preparatory and temporary; that eventually they will become unnecessary, and a full and free entrance be obtained for Indians into the public school system of the country. It is to this end,” the “Rules” continued, that “all officers and employees of the Indian school service should work” (in Bremner 1971, 2: 1354). Although Native Americans could obtain a “full and free entrance” to all public schools in the United States—as African Americans could not—on those occasions when they availed themselves of that right, they were not always welcomed or well served. Indeed, as Wilbert Ahern has written, “The local public schools to which 53% of Indian children went in 1925, were even less responsive to Indian communities than the BIA schools” (1996 88). And some of the Indian Office’s Catholic schools, from about the 1880s through the 1960s, as we will see, provided their own particular forms of disservice to their Native students.

In her study of the St. Joseph’s Indian boarding school in Kashena, Wisconsin, Sarah Shillinger affirms that “Assimilation was an important, if not a more important goal than education to the supporters of the boarding-school movement” (2008 95). Her conclusion, however, is that the boarding schools’ “results were closer to an integration of both cultural systems [Indian and white] than … to assimilation in

-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Actualités

-

Lifestyle

-

Presse jeunesse

-

Presse professionnelle

-

Pratique

-

Presse sportive

-

Presse internationale

-

Culture & Médias

-

Action et Aventures

-

Science-fiction et Fantasy

-

Société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage