-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage

La lecture à portée de main

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisDécouvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisEn savoir plus

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

En savoir plus

Description

Sujets

Informations

| Publié par | Azrieli Foundation |

| Date de parution | 01 septembre 2014 |

| Nombre de lectures | 2 |

| EAN13 | 9781897470862 |

| Langue | English |

Informations légales : prix de location à la page 0,0300€. Cette information est donnée uniquement à titre indicatif conformément à la législation en vigueur.

Extrait

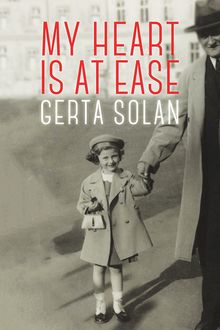

My Heart Is At Ease

Gerta Solan

The Azrieli Series of Holocaust Survivor Memoirs

Naomi Azrieli, Publisher

Jody Spiegel, Program Director

Arielle Berger, Managing Editor

Elizabeth Lasserre, Senior Editor, French-Language Editions

Aurélien Bonin, French-Language Education, Outreach and Events

Catherine Person, Quebec Educational Outreach and Events

Elin Beaumont, English-language Educational Outreach and Events

Tim MacKay, New Media and Marketing

Susan Roitman, Executive Coordinator (Toronto)

Mary Mellas, Executive Coordinator (Montreal)

Eric Bélisle, Administrative Assistant

Mark Goldstein, Art Director

François Blanc, Cartographer

Bruno Paradis, Layout, French-language editions

Contents

The Azrieli Series of Holocaust Survivor Memoirs

Series Preface: In their own words...

About the Glossary

Introduction

Dedication

Author’s Preface

A Carefree Childhood

Facing the Unknown

Surviving the Unbearable

Going Home

The Post-war Years

Another Difficult Political Era

Uninvited Visitors

Culture Shock

Establishing Ourselves

Milestones

Coping with Loss

On My Own

Epilogue

Glossary

Photographs

Copyright

About the Azrieli Foundation

Also Available

Series Preface: In their own words...

In telling these stories, the writers have liberated themselves. For so many years we did not speak about it, even when we became free people living in a free society. Now, when at last we are writing about what happened to us in this dark period of history, knowing that our stories will be read and live on, it is possible for us to feel truly free. These unique historical documents put a face on what was lost, and allow readers to grasp the enormity of what happened to six million Jews – one story at a time.

David J. Azrieli , C.M., C.Q., M.Arch

Holocaust survivor and founder, The Azrieli Foundation

Since the end of World War II , over 30,000 Jewish Holocaust survivors have immigrated to Canada. Who they are, where they came from, what they experienced and how they built new lives for themselves and their families are important parts of our Canadian heritage. The Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program was established to preserve and share the memoirs written by those who survived the twentieth-century Nazi genocide of the Jews of Europe and later made their way to Canada. The program is guided by the conviction that each survivor of the Holocaust has a remarkable story to tell, and that such stories play an important role in education about tolerance and diversity.

Millions of individual stories are lost to us forever. By preserving the stories written by survivors and making them widely available to a broad audience, the Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program seeks to sustain the memory of all those who perished at the hands of hatred, abetted by indifference and apathy. The personal accounts of those who survived against all odds are as different as the people who wrote them, but all demonstrate the courage, strength, wit and luck that it took to prevail and survive in such terrible adversity. The memoirs are also moving tributes to people – strangers and friends – who risked their lives to help others, and who, through acts of kindness and decency in the darkest of moments, frequently helped the persecuted maintain faith in humanity and courage to endure. These accounts offer inspiration to all, as does the survivors’ desire to share their experiences so that new generations can learn from them.

The Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program collects, archives and publishes these distinctive records and the print editions are available free of charge to libraries, educational institutions and Holocaust-education programs across Canada. They are also available for sale to the general public at bookstores. All revenues to the Azrieli Foundation from the sales of the Azrieli Series of Holocaust Survivor Memoirs go toward the publishing and educational work of the memoirs program.

The Azrieli Foundation would like to express appreciation to the following people for their invaluable efforts in producing this book: Sherry Dodson (Maracle Press), Sir Martin Gilbert, Farla Klaiman, Andrea Knight, Therese Parent, and Margie Wolfe and Emma Rodgers of Second Story Press.

About the Glossary

The following memoir contains a number of terms, concepts and historical references that may be unfamiliar to the reader. For information on major organizations; significant historical events and people; geographical locations; religious and cultural terms; and foreign-language words and expressions that will help give context and background to the events described in the text, please see the Glossary .

Introduction

Gerta Solan (n é e Gelbkopf) was born in Prague in 1929. She grew up an only child in a large, extended Jewish family whose branches connected kin in Prague, Brno and Vienna, an extended family that crisscrossed national borders and cultural boundaries. Her parents, Grete and Theodor Gelbkopf, were as much at home in Vienna as they were in Prague.

During Gerta’s childhood, Prague was the capital of Czechoslovakia, a state created in 1918 and made up of territories from both the Austrian and Hungarian part of the former Habsburg Empire. 1 The First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–1938) was a multinational state dominated by Czechs and Slovaks, but inhabited by significant minority populations of Germans, Hungarians, Jews, Ruthenians and Poles. In total, Jews made up less than 3 per cent of Czechoslovakia’s population. The majority of the country’s Jews lived in the eastern regions, Slovakia (136,737) and Subcarpathian Ruthenia (102,542). In the west, the Bohemian Lands (Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia) were home to more than 117,000 Jews. The largest Jewish community in this part of the country was in Prague.

As a result of the post-World War I amalgamation of these culturally diverse territories, the Jews of Czechoslovakia belonged to many linguistic, national and social communities. Religious differences between Jews, ranging from non-observant to Orthodox and Hasidic, were very significant. In the Bohemian Lands, Czech and German were the dominant languages among Jews while in Slovakia and further east, Jews spoke Hungarian, German, Slovak and Yiddish. 2

In many ways, Gerta Solan’s parents and their families embodied typical characteristics of Jewish society in the Bohemian Lands. They were urban, acculturated, German- and Czech- speaking and middle class, and had strong social and professional links to Vienna, the former Habsburg capital, now the capital of Austria. Gerta’s parents had deep ties to Vienna. Her mother’s family, the Roubitscheks, was from Bohemia, but her mother, Grete, and her five siblings were born and grew up in Vienna. Gerta’s father, Theodor Gelbkopf, was from Br ü nn/Brno, the largest city in Moravia, and went to Vienna in pursuit of education. After they married in 1928, Grete and Theodor settled in Prague. Thus, even though the border had changed, the social and cultural ties that existed between villages and cities in the Bohemian Lands and the former imperial capital in Vienna persisted, held together not only by a shared German-language culture but also by extended family connections. While Prague and Vienna were capitals of Czechoslovakia and Austria respectively, economic, cultural and familial bonds remained strong.

The 1920s and ’30s in Czechoslovakia are often remembered as a “golden age,” a respite between two devastating wars. In an unstable and crisis-ridden Central Europe, Czechoslovakia was a relatively stable and prosperous democracy. For Jews, it was important that the country’s elite rejected the calls for state-sponsored antisemitism that occurred elsewhere. Indeed, conditions for Jews were radically different from those in neighbouring Hungary, Poland and, of course, Germany. Antisemitism, however, was not absent in Czechoslovakia. 3 For example, some Czech and Slovak politicians and journalists accused Jews of being disloyal citizens and agents of the old dominant elites, the country’s German and Hungarian minorities. Some Czechs criticized Jews for using the German language, accusing them of deep-seated hostility toward Czechs and playing up antisemitic stereotypes to cast Jews as dangerous and perpetual outsiders. Similarly, in Slovakia, social, economic and religious tensions between Jews and Catholics persisted and by the 1930s were fuelled by some Slovak nationalists’ deepening ideological and political ties to Nazi Germany. 4

By the mid-1930s, political tensions increased between the Czech-dominated central government in Prague, Slovak nationalists and the country’s large German minority. In Prague, as seven-year-old Gerta started school, her teachers instructed her and her classmates not to speak German in public so as not to become targets of people’s anti-German opinions. Although there were efforts to resolve the internal strife, Adolf Hitler, the leader of Germany, pre-empted such efforts by securing an internationally-sanctioned annexation of Czechoslovakia’s western border regions, the Sudetenland, in October 1938.

During the months of political crisis and uncertainty that followed, thousands of refugees, many of whom were Jews, began pouring into the Bohemian Lands from the border areas. The Jewish refugees were not welcomed by the new, more radical Czech nationalist government in Prague or by many ordinary Czechs. Now, along with thousands of Jewish refugees from Austria and Germany, who

-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Actualités

-

Lifestyle

-

Presse jeunesse

-

Presse professionnelle

-

Pratique

-

Presse sportive

-

Presse internationale

-

Culture & Médias

-

Action et Aventures

-

Science-fiction et Fantasy

-

Société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage