-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage

La lecture à portée de main

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisEnemy in Italian Renaissance Epic , livre ebook

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisEn savoir plus

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

En savoir plus

Description

Sujets

Informations

| Publié par | University of Delaware Press |

| Date de parution | 01 mai 2019 |

| Nombre de lectures | 0 |

| EAN13 | 9781644530023 |

| Langue | English |

Informations légales : prix de location à la page 0,1950€. Cette information est donnée uniquement à titre indicatif conformément à la législation en vigueur.

Extrait

THE EARLY MODERN EXCHANGE

Series Editors

Gary Ferguson, University of Virginia; Meredith K. Ray, University of Delaware

Series Editorial Board

Frederick A. de Armas, University of Chicago; Valeria Finucci, Duke University; Barbara Fuchs, UCLA; Nicholas Hammond, University of Cambridge; Kathleen P. Long, Cornell University; Elissa B. Weaver, Emerita, University of Chicago

The Early Modern Exchange publishes studies of European literature and culture (c. 1450–1700) exploring connections across intellectual, geographical, social, and cultural boundaries: transnational, transregional engagements; networks and processes for the development and dissemination of knowledges and practices; gendered and sexual roles and hierarchies and the effects of their transgression; relations between different ethnic or religious groups; travel and migration; textual circulation / s. The series welcomes critical approaches to multiple disciplines (e.g., literature and law, philosophy, science, medicine, music, etc.) and objects (e.g., print and material culture, the visual arts, architecture), the reexamination of historiographical categories (such as medieval, early modern, modern), and the investigation of resonances across broad temporal spans.

Titles in the Series

Involuntary Confessions of the Flesh in Early Modern France, Nora Martin Peterson

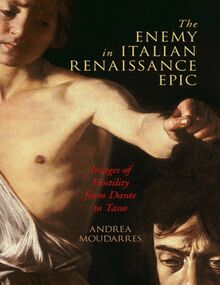

The Enemy in Italian Renaissance Epic: Images of Hostility from Dante to Tasso, Andrea Moudarres

The Enemy in Italian Renaissance Epic

Images of Hostility from Dante to Tasso

Andrea Moudarres

U NIVERSITY OF D ELAWARE P RESS

Newark

Distributed by the University of Virginia Press

University of Delaware Press

© 2019 by Andrea Moudarres

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2019

ISBN 978-1-64453-000-9 (cloth)

ISBN 978-1-64453-001-6 (paper)

ISBN 978-1-64453-002-3 (e-book)

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this title.

Cover art: Detail from David with the Head of Goliath, Caravaggio, 1606. (Galleria Borghese, Rome, Lazio, Italy/Bridgeman Images)

From you, O goddess, from you the winds flee away, the clouds of heaven from you and your coming; for you the wonder-working earth puts forth sweet flowers, for you the wide stretches of ocean laugh, and heaven grown peaceful glows with outpoured light.

—Lucretius, De rerum natura

Contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

1. Between Fathers and Sons: Sowers of Enmity in Inferno 28

2. The Enemy within the Walls: Treachery, Pride, and Civil Strife in Pulci’s Morgante

3. The Enemy as the Self: Madness and Tyranny in Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso

4. The Geography of the Enemy: Christian and Islamic Empires from the Fall of Constantinople to Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata

Epilogue: The Mirror of the Friend?

Notes

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgments

This book began as a doctoral dissertation at Yale University under the enlightening supervision of Giuseppe Mazzotta. His voracious intellectual curiosity has been—and always will be—a source of inspiration. Millicent Marcus and David Quint provided generous feedback and probing criticism that helped me rethink the structure of this project. Without Piero Boitani’s encouragement and unflinching support over the last twenty years, I would not have crossed the Pillars of Hercules. His course on Ulysses at the University of Rome, “La Sapienza,” ignited my passion for the study of literature. I am also indebted to my teachers, colleagues, and friends at the University of Notre Dame: Zyg Barański, Ted Cachey, Margaret Meserve, Christian Moevs, Colleen Ryan, Patrick Vivirito, and John Welle. They created a stimulating and welcoming atmosphere during the two years in which South Bend was my home.

My colleagues at the UCLA Department of Italian have fostered a supportive environment without which I would not have been able to complete this book: Massimo Ciavolella, Thomas Harrison, Lucia Re, Pete Stacey, Dominic Thomas, Elissa Tognozzi, and Stefania Tutino. I also wish to express my gratitude to other UCLA colleagues in neighboring departments: Carol Bakhos, Lia Brozgal, Jean-Claude Carron, Nina Eidsheim, Barbara Fuchs, Robert Gurval, David Kim, Efraín Kristal, Benjamin Madley, Kirstie McClure, Joseph Nagy, Anthony Pagden, Davide Panagia, David Schaberg, Giulia Sissa, Zrinka Stahuljak, Bronwen Wilson, and Maite Zubiaurre. Their wisdom and collegiality have made UCLA an ideal setting for me to learn, teach, and write. Among the colleagues whose suggestions and criticism over the last several years have improved this book I am particularly grateful to Albert Ascoli, Jo Ann Cavallo, Jim Coleman, Laura Giannetti, Toby Levers, David Lummus, Barry McCrea, Vittorio Montemaggi, Pina Palma, Gabriele Pedullà, Kristin Phillips-Court, Diego Pirillo, Alessandro Polcri, Guido Ruggiero, Arielle Saiber, Justin Steinberg, Walter Stephens, Nora Stoppino, Francesca Trivellato, and Jane Tylus.

I am also grateful to the reviewers of this manuscript—their suggestions have significantly strengthened this project—and to Julia Oestreich, who has provided indispensable guidance throughout the publication process. I also owe a debt of gratitude to Valeria Finucci and Meredith Ray, who have supported the publication of this book in The Early Modern Exchange Series for the University of Delaware Press. Thanks to Julia Boss, who has extensively commented on the entire manuscript, and my research assistants at UCLA: Nina Bjekovic, Sarah Cantor, Allison Collins, Cristina Politano, and Joseph Tumolo, all of whom have provided much needed help at various stages of this project. Research for this book has been made possible by an ACLS New Faculty Fellowship and a UCLA Faculty Career Development Award.

Most of all, I am grateful to my loving family. Special thanks to my wife Christiana, who has read and seen this project develop since its inception. To my sister Laura I am especially grateful for her thoughtfulness and wit. I dedicate this book to my parents, Pina and Haisam, who have supported me all along.

An earlier version of a section of chapter 1 was published as a journal article, “Beheading the Son: Mohammed and Bertran de Born in Inferno 28,” California Italian Studies 5:1 (2014): 550–65. Chapter 2 includes a short and much revised version of an essay published as, “The Giant’s Heel: Pride and Treachery in Pulci’s Morgante, ” MLN 127.1 (2012): 164–72; an earlier version of a section of chapter 4 was published as a journal article, “Crusade and Conversion: Islam as Schism in Pius II and Nicholas of Cusa,” MLN 128.1 (2013): 40–52, © The Johns Hopkins University Press. Chapter 4 includes a revised section published as a book chapter, “The Geography of the Enemy: Old and New Empires between Humanistic Debates and Tasso’s Gerusalemme liberata ,” in New Worlds and the Italian Renaissance: Contributions to the History of European Intellectual Culture, ed. Andrea Moudarres and Christiana Purdy Moudarres (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 291–332. My thanks to these publishers for their permission to reprint this material.

Introduction

I N THE OPENING LINES of his unfinished historical epic Civil War, the Roman poet Lucan deploys a graphic bodily metaphor of self-mutilation to introduce the subject of his poem. Writing at the time of Nero, in the first century CE, Lucan takes a strikingly anti-imperial and anti-Virgilian position on the political upheaval that led to the rise of the Augustan Principate. He depicts the Roman commonwealth as a body gutting itself by means of the internecine conflict between Julius Caesar and Pompey, his son-in-law. At the same time, since the city of Rome was caput mundi (literally, “head of the world,” as Lucan writes in Civil War 2.655), a war that eviscerated Rome would, by extension, decapitate the world order that existed before the emergence of the Empire: “Of war I sing, war worse than civil, waged over the plains of Emathia, and of legality conferred on crime; I tell how an imperial people turned their victorious hands against their own vitals; how kindred fought against kindred; how, when the compact of tyranny was shattered, all the forces of the shaken world contended to make mankind guilty; how standards confronted hostile standards, eagles were matched against each other, and pilum threatened pilum” ( Civil War 1.1–7). 1 The self-inflicted wound in Rome’s political body vividly captures the institutional disintegration of the Republic: Lucan thus exposes the ugly truth about the war to which Virgil only briefly alludes in the Aeneid. In a well-known passage from book 6 of Virgil’s work, Aeneas descends to Hades to encounter his father Anchises, who prophecies Rome’s imperial future, issuing an ex post facto warning to his descendants ( “pueri” ) Caesar and Pompey not to engage in civil—and fratricidal—combat. Using a corporeal image that Lucan would intensify to more poignant effect in the above-cited passage, Anchises states: “Steel not your hearts, my sons, to such wicked war nor vent violent valour in the vitals of your land” [“ne, pueri, ne tanta animis adsuescite bella / neu patriae validas in viscera vertite viris”] ( Aeneid 6.832–33). 2 Of course, by the time Virgil’s Anchises delivers his rueful admonition, Caesar and Pompey have already slashed Rome’s viscera, setting the stage for Augustus’s rise to power and for the Aeneid ’s apparent celebration of the emperor. In the proem of Civil War, Lucan adopts the bodily image of Anchises’s warning with a significant modification, which underscores the self-destructive quality of this enmity: it is not just the conflict’s two protagonists, but notably the Roman people (“populus”), who eviscerated the fatherland (“patria”). Lucan’s emphasis in the subsequent lines on the city’s symbols of power—the standards (“signa”), the eagles (“aquilas”), and the javelin (“pilum”)—further highlights the mirror-like image of the

-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Actualités

-

Lifestyle

-

Presse jeunesse

-

Presse professionnelle

-

Pratique

-

Presse sportive

-

Presse internationale

-

Culture & Médias

-

Action et Aventures

-

Science-fiction et Fantasy

-

Société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage