-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage

La lecture à portée de main

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisDécouvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisEn savoir plus

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

En savoir plus

Description

Sujets

Informations

| Publié par | Clemson University Press |

| Date de parution | 31 juillet 2023 |

| Nombre de lectures | 0 |

| EAN13 | 9781638041030 |

| Langue | English |

Informations légales : prix de location à la page 0,0750€. Cette information est donnée uniquement à titre indicatif conformément à la législation en vigueur.

Extrait

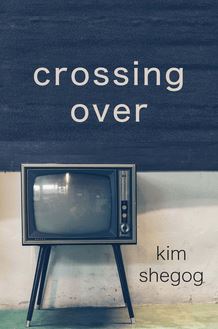

crossing

over

As a partnership between Clemson University Press and the Converse College Low Residency MFA program, this series publishes poetry collections, short-story collections, and creative nonfiction.

crossing

over

kim

shegog

© Kim Shegog, 2022

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-63804-103-0

Published by Clemson University Press.

Visit our website to learn more about our publishing program:

www.clemson.edu/press .

Typeset by Kirstin O’Keefe with the assistance of Emily Rose Campbell, Caroline Cardoso, Sadie Chafe, Liam Conley, Alex Crume, Mary Dixon, Whitney Edgerly, Tyrell Fleshman, Jordan Green, Emma Hammel, AnnaRae Hammes, Olivia Hanline, Anna Higgins, Mary Frances Huggins, Cece Lesesne, Bucky O’Malley, Michael Ondrus, Clarence Orr, Kathryn Rabon, Fran Smith, and Jordan Thurman.

For Eli and Samuel

Speak, for your servant is listening.

1 Sam. 3:10

Contents

Crossing Over

Glory

Goodbye Alice

Sweet Smoke

Desire

Play

There Isn’t Any More

Stay

Work Gloves

Breath to Bones

Acknowledgments

Crossing Over

F amily is a fine thing until people get in the way. Patty, surprised by her revelation, explored each face trapped at the table, a web of young and old and greats and grands, all with faces reddened by hot dishes or hot liquor or both. Fools and drunks, including some of the women, and one or two maybe worse, but a little bit of each flowed through her veins. They could be kind or even captivating, a thought she liked to keep in her mind. Patty’s father was one of these, flawed but forgivable at times. It helped that his dark chestnut-colored eyes and matching hair made him handsome. A fact she knew because one of her girlfriends had told her so.

“Mama’s the one named me Georgia,” he said, raising his cleft chin. “Took me two years, but I earned it. Virgil and Louis—they never made it past their first birthdays. When me and Mother and Papa made it over the Tennessee line in 1925, she slapped me on the back and claimed I was her Georgia boy.”

The only thing he did well when he was drinking was tell a story, and there was no better time to tell a story than at the dinner table on Thanksgiving when there was nowhere to go even if somebody wanted to.

They’d all heard Georgia’s story before, many times. He told it every year, but they laughed and slapped the table in between mouthfuls of fried apples and cornbread dressing. Patty laughed hardest. It was a treat for the fifteen-year-old to observe her father acting like anyone else’s father for a little while. Her mother, too, was normal. She sat with a shy grin, smiling as the crowd gorged themselves on her dishes, her craft glorified through bulging cheeks and grinding teeth.

Like most of her girlfriends’ parents, Patty’s mother and father met at church, though their meeting had been a little different than most. Her mother’d caught him smoking in the garden shed by the cemetery. After church, she’d walked through the grass, weaving in between the gravestones, waiting for her mother to finish chatting with the ladies about hats and gloves and such. She found him reclined on the cement floor, his back propped against a few canvas sacks. He offered her a cigarette, a non-filter, her first of any kind, and they sat in the shed, trapped in silver smoke and infatuation. They married the next year when she was supposed to be a junior in high school, but she quit. Georgia told her schooling didn’t matter anyway. He’d only made it through the sixth grade, and he had a good position on the assembly line at the carpet plant.

Grandma Ruth sat across the table from Patty. Patty stared, moved her gaze to her mother and then back to her grandmother. These two women shared nothing, she confirmed. Grandma Ruth was a good deal smaller than Patty’s mother, and her face, blessed with high, tight cheekbones, made Patty think of Artemis, or any one of those beautiful Greek goddesses she’d read about in school. Her scent, a perfume blend of cloves and cut strawberries, radiated a feminine warmth around her. Patty didn’t think of anyone else when she looked at her mother. Hair in a bun. Curved shoulders. Apron strings in a knot. Scuffed heels. Always, only, a mother.

Besides her beauty, Grandma Ruth had worked. Not like Patty’s mother with her simple cooking and cleaning and washing. She’d worked at a manufacturing job in Dalton, helping to design embroidery patterns for quilts, grand peacocks and lily flowers her specialties. She still kept her design booklets in the cedar chest at the foot of her bed. Patty’d found them a few years earlier while spending the night. She’d asked her grandmother to show her pictures of her grandfather before he’d lost his good sense and run off.

“You’re an artist,” Patty said to her grandmother after listening to her share part of her history. “A real, live artist and my grandma, too.” To compensate for her embarrassment, Grandma Ruth had buried the pattern book under her red fox stole and brass photo frames. After closing the lid without a word, she had climbed into bed in her housecoat.

“Patty. Did you hear your Uncle Billy?” her mother asked, wiping her thin lips with her clean cloth napkin. “He’s talking to you.”

Patty turned her head toward her uncle. No matter her response, it’d be the wrong thing. After all, what did children know? A statement he’d made before.

The truth was Uncle Billy was jealous of his older brother, Georgia. For Patty, it was plain to see. Uncle Billy was as round as a tire on a school bus and bald besides. He did make a pile of money somewhere though, and the money earned him a parade of lady friends, some from another state. “Couldn’t decide which one should have the pleasure,” he’d explained when Georgia asked him where his date was for supper. Last year, it was Rose from Nashville who swore her cousin knew Johnny Cash. Patty and her father shared a love for the country singer, sometimes singing a duet to “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town,” when it came on the radio in the Pontiac.

“Don’t bother her, brother,” Georgia said, slapping Billy on the back. “She’s always thinking about one thing or another. Half the time she don’t know what’s real and what’s not,” Georgia said, downing the last bit of bourbon in his glass.

His audience grinned like Sunday ushers with the collection plates, nodding in approval of his contribution.

Patty’s cheeks spiked red. She turned an apple slice on its side with her fork, gauging it into several pieces. She knew more than they gave her credit for.

First, she knew most husbands and wives loved each other. She knew because she saw it on television, re-runs of The Donna Reed Show for one. And one night when she’d joined her friend Kay for supper, she saw Kay’s father pull out the chair for his wife. Then Patty was bringing the dirty dishes into the kitchen, and she saw him rubbing her shoulders. Patty couldn’t remember seeing her parents do anything of the sort. The closest they came was on a Sunday, years ago, and they were all in the living room reading the newspaper. Patty sat on the floor with the funnies while her mother and father sat on opposite ends of the couch. Patty’s mother asked for the obituaries, which Georgia passed to her. When she took hold of the paper, her fingers brushed the back of his hand, and she kept them there longer than was necessary. His cheeks turned red, like Patty’s often did, his shoulders relaxed, and he was satisfied for a moment.

Second, she knew fathers weren’t supposed to drink as much as hers although it did help liven things up sometimes, and she knew mothers, for the most part, liked having daughters, that they should do things together, like go to church, and they should have picnics on the weekends in warm weather like some of her friends’ families. It shouldn’t be Grandma Ruth taking Patty to church. The four of them should be going together. It’d be better if her parents argued, raised their voices at one another, anything instead of what they did in silence: him going to work and coming home, sometimes working on the furnace or mowing the yard, her getting up the breakfast dishes and hanging the clothes on the line, once in a while asking Patty how her day was at school. Patty’s home was a ghost town out of a Western.

“Georgia, don’t tease her so,” Grandma Ruth said, patting his shoulder. “She’s just a young thing.” Even Grandma Ruth, Patty’s favorite, believed her to be a child, all ignorance and misunderstanding.

“Everybody eat up.” Patty’s mother passed the bowl of snap beans to Grandma Ruth, who took none, sitting the bowl on the table.

“You’ve outdone yourself again,” Uncle Billy said, picking up the bowl. “Georgia, I tell you, you are a lucky man.” He poured a heaping spoonful of beans onto his plate.

“Don’t I know it. Lucky from the beginning to have such a fine wife.”

“Mother, your biscuits are perfect,” Patty’s mother said, breaking one open, placing the two halves on her plate. “I never could get mine to taste like yours.”

“I didn’t cook. You know that,” said Grandma Ruth. “The one thing I did well was those biscuits. I thought I’d shown you what to do. I know Patty and I made them together before. She can teach you. Surely she remembers.”

“I might have her do that,” Patty’s mother said, spinning the two halves with her fork.

“Patty baked biscuits?” Georgia asked, reaching for the gravy boat. “I heard you tell one of your little friends how you’d never be like your mama, wasting her time in the kitchen.”

Again, Patty’s cheeks burned. If she’d keep her eyes low and focused on her plate, nobody’d notice. She did say that but only to Kay. They’d been riding their bicycles up the driveway when she’d told her she wanted to be a nurse and not waste her time

-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Actualités

-

Lifestyle

-

Presse jeunesse

-

Presse professionnelle

-

Pratique

-

Presse sportive

-

Presse internationale

-

Culture & Médias

-

Action et Aventures

-

Science-fiction et Fantasy

-

Société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage