-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage

La lecture à portée de main

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisDécouvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Je m'inscrisEn savoir plus

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

En savoir plus

Description

- Advance reader copies

- Targeted endorsements

- Targeted reviews in book trade publications

- Targeted reviews in publications and websites covering science, medicine, health, history, and general interest

- Targeted reviews in major newspapers

- Targeted radio, and podcast interviews

- Regional author tour in Austin, San Antonio, Dallas, New Orleans

- Promotion on author's website

- Social media promotion

Beware the pronouncements from medical authorities on high…

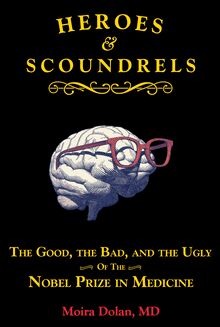

The good, the bad, and the ugly of the winners of the Nobel Prize in Medicine are explored in these entertaining biographies of the world’s most highly recognized scientists. From unapologetic Nazis to dedicated humanitarians who carried out prize-winning research while being resistance fighters or peace activists, these engaging true stories reveal the depths of both the human strength and depravity of the people who forged medical progress in the twentieth century.

In Heroes & Scoundrels (Volume 2 in the Boneheads and Brainiacs series), author and medical historian Moira Dolan, MD, continues her fascinating exploration of Nobel Prize in Medicine winners, focusing on the years 1951–1975. The book’s many biographies include the delightful discoveries of a honeybee researcher who persisted through the carpet-bombing of Munich, in-depth reflections on the nature of consciousness from Nobel neuroscientists, and even wild, hard-to-believe self-experimentation in the name of medical progress.

Heroes & Scoundrels also provides readers with an eye-opening “behind the scenes” look at what one Nobel winner described as “a few odd crooks” in the Nobel Prize business of the post-War era, including researchers engaged in medical research dishonesty and fraud, and self-important scientists who leveraged their notoriety to influence public health affairs. The role of Nobel Prize winners is revealed in public debates about everything from water fluoridation to “good genes” and “bad genes.” One laureate wondered, “whether mad scientists should really be allowed to police themselves” in light of the lack of informed consent for vaccine research and modified viruses escaping from labs.

As put by another laureate, the “medical priesthood” is due for some critique, and this book will get you thinking.

Preface

Chapter 1: Yellow Jack

Chapter 2: Dirty Business

Chapter 3: Squiggles and Gold

Chapter 4: The Polio Researchers

Chapter 5: Like The Priest At A Wedding

Chapter 6: Self-experimentation

Chapter 7: Drugs

Chapter 8: From Wahoo to Outer Space

Chapter 9: The Men (and Women) of DNA

Chapter 10: Self and Non-self

Chapter 11: Postal Worker Wins The Nobel Prize

Chapter 12: The Wonder Boys

Chapter 13: What Nerve

Chapter 14: The Cholesterol Discoveries

Chapter 15: The French Freedom Fighters

Chapter 16: The Cancer Detectives

Chapter 17: The Visionaries

Chapter 18: Making Protein

Chapter 19: Viruses Everywhere

Chapter 20: Brain Chemicals

Chapter 21: The Midwestern Genius

Chapter 22: Untangling Antibodies

Chapter 23: The Birds and the Bees

Chapter 24: Inside the cell

Chapter 25: Infected by Viruses

Afterword

Winners of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

Sujets

Informations

| Publié par | Linden Publishing |

| Date de parution | 23 août 2022 |

| Nombre de lectures | 0 |

| EAN13 | 9781610354028 |

| Langue | English |

| Poids de l'ouvrage | 1 Mo |

Informations légales : prix de location à la page 0,0650€. Cette information est donnée uniquement à titre indicatif conformément à la législation en vigueur.

Extrait

HEROES & SCOUNDRELS

T HE G OOD, THE B AD, AND THE U GLY

OF THE

N OBEL P RIZE IN M EDICINE

Moira Dolan, MD

Fresno, California

Heroes & Scoundrels: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of the Nobel Prize in Medicine

© copyright 2022 Moira Dolan, MD

Cover image courtesy Shutterstock/Jolygon

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-161035-393-9

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Linden Publishing titles may be purchased in quantity at special discounts for educational, business, or promotional use. To inquire about discount pricing, please refer to the contact information below.

For permission to use any portion of this book for academic purposes, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at www .copyright .com

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data on file

Linden Publishing, Inc.

2006 S. Mary

Fresno, CA 93721

www .lindenpub .com

Contents Preface Chapter 1: Yellow Jack Chapter 2: Dirty Business Chapter 3: Squiggles and Gold Chapter 4: The Polio Researchers Chapter 5: Like the Priest at a Wedding Chapter 6: Self-Experimentation Chapter 7: Drugs Chapter 8: From Wahoo to Outer Space Chapter 9: The Men (and Women) of DNA Chapter 10: Self and Nonself Chapter 11: Postal Worker Wins the Nobel Prize Chapter 12: The Wonder Boys Chapter 13: What Nerve Chapter 14: The Cholesterol Discoveries Chapter 15: The French Freedom Fighters Chapter 16: The Cancer Detectives Chapter 17: The Visionaries Chapter 18: Making Protein Chapter 19: Viruses Everywhere Chapter 20: Brain Chemicals Chapter 21: The Midwestern Genius Chapter 22: Untangling Antibodies Chapter 23: The Birds and the Bees Chapter 24: Inside the Cell Chapter 25: Infected by Viruses Afterword Winners of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1951–1975 Index

Preface

Welcome to the continuation of the lively biographies of winners of the Nobel Prize in Medicine begun in my previous book, Boneheads and Brainiacs , which covered the years 1901 to 1950. This volume profiles the prizewinners from 1951 to 1975. As a result, my research was easier, because so much more documentation is available from this period, including many video interviews; more numerous memoirs, biographies, and autobiographies; and treasure troves of the entire collected works of many of these scientists. Thus, the stories of only a quarter century fill as many pages as the first fifty years in Boneheads and Brainiacs .

Another benefit of the abundant documentation was that I was able to discover more about the sidelined players—especially the unrecognized women who conducted much of the prizewinning research themselves or alongside the men who would become Nobel Prize winners. Medical history buffs may have already heard of Rosalind Franklin’s role in the discovery of the structure of DNA, but in these pages you will also meet Filomena Nitti, Esther Zimmer, Marianne Grunberg-Manago, Elizabeth Keller, Martha Chase, Ruth Hubbard, Betty Press, and Marguerite Vogt. In the first fifty years of the prize, Gerty Cori was the only woman to win, when she shared the award in 1947 with her husband, Carl Cori. In the next twenty-five years, all of the winners were male and white with the exception of Har Gobind Khorana, the only medicine prizewinner so far to come from India, also male.

Some themes are carried over from the first half century of the prize, such as the influences of the two world wars. In these pages, you will meet two winners who were card-carrying members of the Nazi Party, one famous American racist, a host of scientists who escaped the war as academic and political refugees, and amazing scientists who were resistance fighters. Other carry-overs from the first book are episodes of unethical behavior—notably taking credit where none is due—and, on the other end of the spectrum, instances of scientists not taking responsibility for goofs or fraud committed by others in their labs.

While some of the prizewinning research was truly delightful, like the discoveries of the amazing significance of the dance of the honeybees, other research was at best unoriginal, even leading a couple of these winners themselves to wonder why they got the prize. These are instances where advances in techniques led to mundane research yielding results largely due to nothing more than the application of good lab technique in a workmanlike fashion rather than any brilliant insight or novel approach to a scientific problem. Even the most famous of these accomplishments, the discovery of the structure of DNA, would have been worked out eventually by other researchers sooner or later, probably within weeks to months—it’s just that Watson, Crick, and Wilkins beat everybody else to it.

The period covered here saw a shift in the nature of the scientific works that were recognized by a Nobel Prize. Discoveries in the first half of the twentieth century—such as penicillin, vitamin C, and estrogen—were more obviously physical and usually more directly applicable to patient care. In the next quarter-century, research largely turned toward entities visualized only with the aid of an electron microscope, or, more commonly, only indirectly identified and deduced through biochemical reactions. This research focused on genetics and viruses above all else. It is often difficult to discern the applicability of many of these discoveries to the everyday life of the health care consumer, but it does seem that the current pandemic has focused attention on these topics.

It is my hope that my readers become interested in the science and are entertained by the human stories.

Enjoy!

Moira Dolan, MD

Austin, Texas, May 2022

1 Yellow Jack

The Nobel Prize in 1951 was awarded to Max Theiler for his discoveries concerning yellow fever and how to combat it. The story of the research into yellow fever is the Nobel Prize’s most deadly tale. It started more than half a century before the prize was awarded, and it is strewn with the illnesses and deaths of many researchers along the way. While it was not unusual for early infectious-disease researchers to fall victim to the illnesses they studied, yellow fever caused more sickness and death in investigators than any other disease.

The yellow fever victim suddenly feels feverish and becomes agitated or irritable. They then get a headache that becomes piercing in intensity and is accompanied by extreme light sensitivity. Within hours, the victim’s temperature goes up to 103 degrees Fahrenheit or higher. At the same time, their pulse slows down, which prevents sweating, and as a result, the victim rapidly becomes dehydrated. The disease next attacks the internal organs, including the kidneys, intestines, liver, and brain. Liver failure causes a buildup of yellow bile, resulting in the skin turning the yellow color of saffroned rice and the whites of the eyes taking on a golden glow—the intense coloration yellow fever is named for. At this point, some patients may begin to slowly recover. The unlucky progress to vomiting black blood and may even bleed from every orifice. The most freakish aspect of yellow fever is how it can affect the brain, causing agonizing delirium and violent convulsions until death. Complete recovery can take weeks or months, and even then, in rare cases a person can die from heart complications years after apparent recovery. Modern medical literature reports yellow fever morality worldwide at over 40 percent.

The infectious disease originated in Africa, where it was endemic—present all the time at low levels. Widely fatal epidemics of the disease at higher levels in specific regions were not recorded until an outbreak in 1648 in Barbados in the eastern Caribbean. More outbreaks followed the next year in Mexico’s Yucatán and in Brazil, after ports in both places received slave ships. The United States saw a yellow fever epidemic the following year in New York, again linked to the arrival of a slave ship. Subsequently, there were epidemics in Philadelphia, where in 1793 some 9 percent of the population was killed; Baltimore; and again in New York City. The 1800s saw major epidemics in Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, New Orleans, and Memphis. Memphis was hit a second time in 1878 with an outbreak more deadly than ever before experienced in the US. The first two cases were recorded at the end of July. By August, yellow fever deaths were so numerous that there was a mass exodus from the city. By September there were only 19,000 residents left, of whom an estimated 17,000 were infected. Ultimately there were over 5,000 deaths. This incident remains the largest and most deadly urban infectious epidemic to hit America, relative to a city’s population. 1

Yellow Fever Compared to Coronavirus

Yellow fever and COVID-19 are both caused by viruses. In Memphis in 1878, yellow fever claimed about 5,000 lives out of a total population of approximately 33,000. In 2020, there were 891 deaths attributed to COVID in Shelby County, which includes Memphis, out of a population of about 937,000.

Ships with the yellow fever on board were quarantined offshore because it was believed that the infected sailors could spread the disease. This gave rise to the disease being called yellow jack, the same name given to the bright-yellow cautionary flag that quarantined ships returning from the tropics were once required to hoist as they waited beyond the harbor until there were no more signs of fever in their crew. When yellow fever brought down several residents of a dockside neighborhood in Memphis, the homes of infected people were boarded up with the victims inside in what turned out to be a futile effort to contain the pestilence. After the occupants were dead, only special body handlers were allowed to touch the rem

-

Univers

Univers

-

Ebooks

Ebooks

-

Livres audio

Livres audio

-

Presse

Presse

-

Podcasts

Podcasts

-

BD

BD

-

Documents

Documents

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

-

Actualités

-

Lifestyle

-

Presse jeunesse

-

Presse professionnelle

-

Pratique

-

Presse sportive

-

Presse internationale

-

Culture & Médias

-

Action et Aventures

-

Science-fiction et Fantasy

-

Société

-

Jeunesse

-

Littérature

-

Ressources professionnelles

-

Santé et bien-être

-

Savoirs

-

Education

-

Loisirs et hobbies

-

Art, musique et cinéma

-

Actualité et débat de société

- Cours

- Révisions

- Ressources pédagogiques

- Sciences de l’éducation

- Manuels scolaires

- Langues

- Travaux de classe

- Annales de BEP

- Etudes supérieures

- Maternelle et primaire

- Fiches de lecture

- Orientation scolaire

- Méthodologie

- Corrigés de devoir

- Annales d’examens et concours

- Annales du bac

- Annales du brevet

- Rapports de stage