Women Who Change the World , livre ebook

Description

- Co-op available

- Galleys available

- Tour info: NY, SF, LA, Denver, Baltimore, Massachusetts, Texas, Atlanta

- National radio campaign: Pursuing NPR-affiliates with programming focused on women and women’s issues.

- Print campaign in top national magazines and newspapers

- Pursuing excerpts in all major publications

- Online/social media campaign

- Most of the women in the book are actively associated with institutions, organizations, and networks that will actively endorse and support the publication of this book. Our publicity and marketing strategy will seek to partner with these institutions for events and online marketing outreach that appeal to their membership base and beyond.

- We’re pursuing nominations for IndieNext and are open to other bookseller and library promotions that are appropriate for the book.

- Author Lynn Lewis is the recipient of many awards and honors, including the National Endowment for the Humanities Oral History Fellowship, the Judge Jack B. Weinstein Fellowship from Columbia University and the Oral History Merit Scholarship from the Oral History Master’s Program at Columbia University.

- One of the activists highlighted in the book, Loretta Ross, has a forthcoming book from Simon and Schuster. Scheduled for publication in 2023, Loretta will be the focus of major A-list publicity and marketing campaign.

- The women who are interviewed in this book come from all over the country, and have very different backgrounds and paths to organizing.

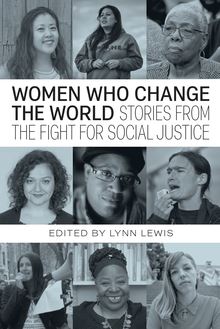

Nine women who have dedicated their lives to the struggle for social justice—movement leaders, organizers, and cultural workers—tell their life stories in their own words. Sharing their most vulnerable and affirming moments, they talk about the origins of their political awakenings, their struggles and aspirations, insights and victories, and what it is that keeps them going in the fight for a better world, filled with justice, hope, love and joy.

Featuring Malkia Devich-Cyril, Priscilla Gonzalez, Terese Howard, Hilary Moore, Vanessa Nosie, Roz Pelles, Loretta Ross, Yomara Velez, and Betty Yu

INTRODUCTION

The women interviewed for this book have played critical roles in contemporary organizing struggles. In that process, they have each participated in making history. They are brilliant thinkers that put theory into action. They generously share some of the personal and political choices that moved them to dedicate their lives to constructing justice. Their stories light a path for all of us.

The nine women interviewed for this collection span a range of identities and life experiences. They have taken different paths into organizing and social justice work. Some took a leap of faith by accepting an invitation to a meeting or a protest, some sought help to solve a problem in their own or their families’ lives. Some were born into movement, deeply conscious of their lineage. Each have stayed involved because they wanted to make sure that the harm caused to them, and to others, would not be repeated.

Over time, they have grown into their own power, learning how to build campaigns, organizations, and coalitions. They have navigated disappointments and victories and they have stayed in the struggle, even if their roles have changed. Their work has shifted narratives and created new frameworks for how we think about the critical issues that impact our lives. Most of the women interviewed are not well known beyond the sectors in which they have worked. They stand on the shoulders of historic figures we have learned about and the millions of others whose names we will never know. It isn’t the famous few who will make the revolution; it is the many who are harmed by oppression and who choose to act and to build political power in community.

Why Focus on Community Organizing?

Organizers listen, strategize, and support the collective analysis and collective action of the many, not the few. Because of them, the rest of us have more choices. Because of them the rest of us have more rights. Because of them the rest of us live with less danger, and because of them we are more free.

Movements for social change require many skill sets and talents. They also require theory and infrastructure. Community organizing is the foundation that all movements for social change rest upon. To quote Frances Goldin, “Without the troops, we have nothing.” Without listening to folks harmed by systems of oppression and welcoming them into a collective process to identify solutions, how do we know what the problems are, what solutions to fight for and what alternatives to build? Some of the women interviewed no longer focus their efforts on organizing. They have tapped into and grown their skills as educators, media makers, and cultural workers, or are holding down other roles within organizations because they determined that was where their contribution to social justice would be more meaningful.

The purpose of organizing with a social justice purpose is to build power with those who don’t have it in order to change the conditions of our lives. That begins with building relationships and community so that we can begin to analyze and strategize together. Through organizing, power is distributed horizontally, not vertically, to be hoarded by a few. As Ella Baker teaches, "What is needed, is the development of people who are interested not in being leaders as much as in developing leadership in others." This requires nurturing a political space that creates the conditions where folks can collectively envision a different social construct and build the skills needed to fight for it. The organizations and formations founded by the women interviewed here are examples of such political spaces. Organizing isn’t only about recruiting people to a meeting or mobilizing people to hold signs during a protest. Organizing is about consciousness shifting and supporting individual and collective leadership. This work requires a range of concrete skills, such as street outreach, messaging, meeting facilitation, relationship building, research, critical analysis, and strategic planning. It requires a combination of strength and humility, agility, vision, patience, emotional labor, deep listening, and love. An organizer is a learner, teacher, artist, planner, friend, media maker, and witness. Through their stories, we learn how each woman discovered those skills within themselves and how their skills were sharpened through collective struggle.

Oral History as an Act of Resistance

Oral History is necessary to complete historical narratives with nuance and detail. For oppressed peoples in particular, oral history is a way to ensure that a more complete history is told, recorded, documented, and accessible. If we want to achieve the social change we desperately need, we must understand how we arrived at our present conditions and create counter narratives so critical to constructing justice. Howard Zinn, in A Power That Governments Cannot Suppress, writes, “To omit these acts of resistance is to support the official view that power only rests with those who have the guns and possess the wealth.” Open-ended questions elicit memories that fill gaps in the historical record, offering the narrators the opportunity to correct, complicate, and contextualize events of the past. Oral history interviews generate qualitative and quantitative data that can be used to sharpen our analysis and to deepen our understanding of history for the purpose of making social change. What is most compelling about oral history is that it creates space for people who have been a participant in history-making to reflect on and to document those reflections as lessons to be shared.

Oral history interviews help to reveal the personal and political journeys of each narrator, rendering their examples relatable and accessible. Their skills and analyses developed over time, as conditions demanded multiple strategies and tactics which tested and taught them and built their resolve to stay in struggle. Each of these oral history interviews teaches movement histories from the perspective of women who participated in shaping them. What did that struggle mean to those who planned and participated in it? What did it take to do that work? What does thoughtful reflection about those events tell us? Each narrator has done work on the use of storytelling and narrative in organizing. Sharing their personal, community, and political histories for this book is a political act.

The meaning of historic events is inherited through stories. These stories shape our identity, assign us a social location, and tell us what to believe is possible for ourselves and our communities. For example, gentrification does not have the same meaning for those who were displaced from substandard housing as it does for those who moved into those renovated brownstones afterwards, or the property owners who built wealth in the process. The stories describing the process and result of gentrification differ depending upon how you are affected—whether you benefitted or were harmed. Inherited memories become the stories and myths that uphold power structures, just as inherited memories of resistance and struggles for social justice can transform our understanding of ourselves and our communities. Oral history is one way for oppressed peoples to identify and to assert counter narratives necessary to complement and contest the written record. Counter narratives won’t right the wrongs of the past, but they can illuminate a path towards a just future. How We Go Home, by Sara Sinclair, and other social justice oriented oral history projects, are examples of the use of oral history to correct the historical record and to reveal the ways history that bleeds into the present. The truth is that we may not always win, but we never will if we don’t organize.

“If history is to be creative, to anticipate a possible future without denying the past, it should, I believe, emphasize new possibilities by disclosing those hidden episodes of the past when, even if in brief flashes, people showed their ability to resist, to join together and occasionally to win.”

The seeds of social justice awakening are often reflected in stories rooted in childhood memory. The issues that initially brought the women interviewed for this book into organizing aren’t the only issues that they have worked on. Their stories map out when and how they engaged with those issues, who they engaged with—including some of the people, organizations, and coalitions they worked with—what choices they made and why, and what conditions allowed them to make those choices and take the risks they took to engage in struggle on the local, state, national, and international levels.

The knowledge that people before us have struggled to end oppression as well as to create spaces of liberation and movement infrastructure inspires us to follow in their footsteps. Stories and examples of resistance may appear as visual symbols, such as Harriet Tubman’s face on the T-shirts of United Workers in Baltimore. They may be chanted after many an organizing meeting, as Assata Shakur’s words often are:

“It is our duty to fight for our freedom.

It is our duty to win.

We must love each other and support each other.

We have nothing to lose but our chains.”

These words and stories bond us to past struggles, and help us to situate ourselves within the arc of history. In The Five Hundred Year Rebellion, Benjamin Dangl documents how the use of oral histories of Indigenous resistance were instrumental in strengthening Indigenous movements in Bolivia today.

“For the THOA (Taller de Historia Oral Andina/Andean Oral History Workshop) and other groups examined here, oral history offered a bridge between generations, a way to share stories of oppression and resistance and, as a result, move people to take action.”

It is in this spirit that this book was first conceptualized. Containing nine interviews, this book is not a representative sample of women organizers. What it does offer is to give each woman interviewed the time to tell their story and for us to listen and learn from them. I am deeply grateful to each of the women interviewed for taking the time to reflect, to share and to teach.

Representation Matters

Systems of oppression intersect and conspire to control women based on gender as well as the other identities we embody. The histories shared by the women interviewed for this collection illustrate how disparate issues are connected, vividly evoking the meaning of intersectionality and systems of oppression and the fact that every issue is a woman’s issue. Racism, gentrification and displacement, domestic violence, rape, reproductive justice, police brutality, homelessness and housing insecurity, migration, climate change, labor and economic justice have been normalized because they are such common facts of life for so many. These injustices, however, weigh most heavily on those who are most marginalized by society—women, people of color, and the working class specifically. Race, colorism, class position, migration status, faith, language, ability, geography, sexual identity and orientation, motherhood, health status, and housing status assign privilege, and shape our daily lives and our relationships with one another. Women with privilege have played a critical role in excluding and oppressing women with less privilege. Racism provides white women with privilege over women of color, and specifically Black and Indigenous women.

For this collection, there were choices to be made. I had a few priorities starting out: diversity in terms of race, geography, age, sexual identity and orientation, and migration status. I wanted to focus on working-class women. Because there are different organizing models based on different theories of change, I wanted to include women with an orientation towards paradigm shifting, transformational organizing that propels us beyond short-term focus on winnable campaigns. I wanted to interview women who were caregivers of children, or other loved ones, and to explore how they balanced those responsibilities while organizing.

Not all identities or issues are represented within this collection of nine oral histories. There is a lot missing, and this collection doesn’t pretend to be a representative sample. The narrators are mostly on the East or West coast, ranging in age from their early thirties to early seventies. While nine interviews won’t cover fifty-two states, there is significantly more representation of East and West Coast narrators living in urban areas than rural, although some originally are from rural areas. Expanding beyond the artificial and colonial borders of the US would have made it even more impossible than it already was to narrow down a list of women to only nine for the purpose of this book. That is the only reason it is limited to women organizers in the United States.

The women interviewed have founded and co-founded organizations, coalitions, and movements that range from reformist to revolutionary. You will learn from their analyses that reform and revolution are not necessarily mutually exclusive, sharpened by years of toiling in the fields of grassroots organizing. Several narrators’ political work subjected them to COINTELPRO tactics during the 1970’s and 1980’s, including political assassinations of comrades and COINTELPRO-like surveillance tactics that continue to this day. While each of the women interviewed for this book has founded or deeply engaged in reformist work within a non-profit structure, their work has not been limited to those structures. Indeed, the women interviewed here explicitly align themselves within a range of anti-racist, anti-fascist, radical politics, and radical values. While these are long-form oral history interviews, all aspects of their work are not given their due space within these pages. I used endnotes sparingly to expand upon something, or someone mentioned in the interview.

Just as we aspire to celebrate small victories and progress as it happens, this book honors women as they create those small and large victories because they move us forward on a path towards a more just world. In that spirit, this book is an invitation to look around and see the women in your lives who are making change. Take the time to listen to their stories, and if you and they are up for it, record and transcribe them. Find out who they are and what moved them to take up the responsibility of being a changemaker. Listen to their reflections and find the lessons within. Take the time to explore feminist archives, such as the one at Smith College or organizational/movement archives such as the SNCC oral history project, or those available through NYU Tamiment or Interference Archives. Documenting and sharing histories of resistance as I write this introduction more urgent with every passing day. The women interviewed for this book are amazing, as are so many countless others in this world. I’m fairly certain that most wouldn’t make that claim, however. Everyone has to also find their way, find their mentors and their inspiration. Their examples mean that we can all find ways to contribute to making this a more just world.

This collection of personal and political movement histories is shared in the hope of inspiring and informing all who reject the systems of oppression that confront us on a daily basis. It is critical to reflect on our place in the struggle for social transformation. Through learning about the choices that others have made, it can help us to understand our own choices and possibilities. If you are engaged in movement work, thank you for being one of many making history. If you aren’t already part of some type of organization for social justice, please find and join one. We need you.

ANNOTATED TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction

The women interviewed for this book have played critical roles in contemporary organizing struggles and in that process, have participated in making history. In the following oral history interviews, they generously share some of the personal and political choices that moved them to dedicate their lives to constructing justice. Oral History is an act of resistance for oppressed peoples because it is a way to ensure that a more complete history is told, recorded, documented, and made accessible. Beyond knowing what happened when oral history reveals the meaning of historic events, from the perspective of those who have shaped them.

Loretta Ross

Loretta Ross is an organizer, movement builder, educator, author, and innovator from the local to the global stage, as a Black feminist working on issues of ending violence against women, reproductive justice, and anti-racism. She reflects on the relationships between race and gender in this interview and traces the emergence of her own consciousness around gender equality, racism, and self-determination. She details her work to build collective power with women of color, including her own choice to stay in the movement after her close friend and political comrade was assassinated in Washington, D.C. and the organizations she worked in were faced with COINTELPRO surveillance and repression. Loretta shares her analysis about the need for social justice movements to welcome folks in, and to educate in order to build relationships, movement, and solidarity. Loretta was born in Temple, Texas and now resides in Holyoke, Massachusetts.

Roz Pelles

Roz Pelles is an organizer, strategist, movement builder, and attorney. Joining the civil justice movement as a young teenager, Roz has organized around issues of civil rights, workers’ rights, police brutality, and anti-racism – connecting these issues to broader issues of social justice and liberation. Organizing within an anti-capitalist and anti-racist framework during a period of white supremacist resurgence across the U.S., she is a survivor of the Greensboro massacre in 1979 and is now the Strategic Advisor to the Poor Peoples Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. Roz shares her political trajectory and analysis of the need for a multi-racial, multi-issue movement developed from the bottom-up and reflects on her organizing philosophy of leading from behind. She describes what it means to balance parenting and family life within the context of organizing – accompanied by government repression and political assassination. Roz was born and raised in Winston-Salem, North Carolina and today resides in Maryland.

Vanessa Nosie

Vanessa Nosie is an organizer and spokesperson for Apache Stronghold and works as an archaeology aide with the San Carlos Apache Tribe Historic Preservation office and Archeology Department. She is Chiricahua Apache, enrolled into the San Carlos Apache tribe and resides on the San Carlos Reservation, which was created as a concentration camp for several Apache tribes, where they were forcibly relocated as prisoners of war. Vanessa links her work to that history of colonization and genocide, which doesn’t remain in the past but continues today. In the following interview, she connects the themes of motherhood and lineage to the history of colonization and racism in the U.S. and the need for an understanding of that history in order to heal and identify solutions. Her organizing work is a struggle for the very survival of the Apache people and Mother Earth and calls for unity among all people to confront the forces of greed and power that threaten us all. Vanessa was born in Phoenix, Arizona, and raised on the San Carlos Reservation, where she resides today.

Betty Yu

Betty Yu is a cultural worker whose work has focused on issues including workers’ rights, immigration, gentrification, police violence, class, race, and media justice. Her work links anti-Asian violence and racism with the racism experienced by Black and Indigenous communities and creates opportunities for education and solidarity. In the following interview, she reflects on her own process of understanding that the issues impacting her family and community existed within the context of broader struggles for social justice, describes how she initially engaged with community organizing as a teenager, reflects on the meaning of belonging and accountability, explores the role of the arts in social justice work to educate and to create space for the changing of hearts and minds, the importance of collaboration with community, and the power of storytelling in popular education to shift narratives as part of an organizing strategy. The daughter of immigrants, Betty was born and raised in New York City, and grew up in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, where she lives today.

Hilary Moore

Hilary Moore is an organizer, educator and author who works within an anti-racist framework that links movements to abolish the police and the military with environmental justice, racial justice, and anti-imperialist struggles in the U.S. and internationally. She draws connections between eco-fascism, white supremacy, policing, the military, and surveillance that forecasts many of the dynamics we see today. In the following interview, she reflects on the process of her own political development and explores the meaning of belonging, creating community and connection. She describes the importance of mentorship and the role of storytelling as a way to build connection, leadership, and movement. Born in Sacramento, California, and raised in rural northern California, Hilary now lives in Louisville, Kentucky.

Malkia Devich-Cyril

Malkia Devich-Cyril is an organizer, activist, movement builder, writer, poet, educator, public speaker, and social justice leader in the areas of Black liberation and digital rights in expansive and profound ways that connect racialized capitalism to the digital economy. Malkia reflects on the responsibility of lineage, conferred by her mother, a leader of the Harlem Chapter of the Black Panther Party. Related to this is the theme of belonging: to family, community, and movement and the importance of narrative struggle to make meaning and build power to change material conditions. At the time of this interview, Malkia was formulating an analysis around the relationship between grief, grievance, and governance as a critical strategy to win freedom. Malkia, who also goes by Mac, was born and raised in New York City and lives in Oakland, California.

Priscilla Gonzalez

The daughter of immigrants, Priscilla Gonzalez is an organizer and certified professional coach who has been instrumental in groundbreaking campaign victories and developing movement building infrastructure in New York City, New York State, and nationally around issues of immigration reform, domestic worker’s rights and ending police violence. Priscilla reflects on the importance of centering relationships in an organizing process as well as the power of storytelling as an organizing strategy to build community, shift narratives and to educate. The importance of lineages, and where we and the movements we work within fit into those lineages, is also explored. Finally, she reflects on the value of learning how to sustain ourselves in movement work, including the importance of creativity and fun. Born and raised in New York City, Priscilla now lives in West Texas.

Terese Howard

Terese Howard is an organizer and educator who has been organizing with houseless people for civil and human rights since 2011. She became involved at the onset of Occupy Denver and is a founder of Denver Homeless Out Loud (DHOL) which was formed to defend the rights of people without housing who are criminalized and targeted by the police for basic human activities. In 2022, she founded a new organization, Housekeys Action Network Denver, that is focused on the organizing with houseless folks to guarantee housing is human right for all. Terese describes the anarchist values that inform her approach to her organizing practice and her life, including mutual aid and the sharing of resources, the need to create horizontal and accountable structures within movement and recognizing that we are in relationship with one another and the planet. She reflects on the significance of relationships, particularly within the context of organizing with unhoused folks, and the need to build solidarity and skills across organizations and movements. Terese was born and raised in Spokane, Washington, and rural Colorado. She now lives in Denver, Colorado.

Yomara Velez

Yomara Velez is an organizer and daughter of immigrants from Puerto Rico and Venezuela. As a single mother attending the U. of Massachusetts, she organized students on welfare to demand access to higher education and better living conditions. She has organized around housing and environmental justice issues in the South Bronx and founded Sistas on the Rise, a collective of young mothers of color. Their work was grounded in transformative practices based on grassroots leadership and uplifted motherhood as an important part of organizing work. After moving to Atlanta, she worked on immigration and economic justice issues, including ten years with the National Domestic Workers Alliance. Yomara describes the importance of relationships, of belonging to community and the significance of women mentors in her life. She reflects upon the need for political education and the leadership of community members in organizing and shares her own process of creating alternatives to oppressive structures – including hierarchical structures in movement organizations – and her own journey home schooling her children as a strategy to build alternatives in our personal lives that reflect the world we want to live in. Yomara was born in Massachusetts and currently lives in Atlanta, Georgia.

Sujets

Informations

| Publié par | City Lights Publishers |

| Date de parution | 29 août 2023 |

| Nombre de lectures | 0 |

| EAN13 | 9780872868977 |

| Langue | English |

| Poids de l'ouvrage | 1 Mo |

Informations légales : prix de location à la page 0,0900€. Cette information est donnée uniquement à titre indicatif conformément à la législation en vigueur.

Extrait